Boston was one of a number of American cities that was able to tune in a new TV station in 1948. But Beantown broadcasts on television pre-dated that by more than 15 years. The station ran into some trouble and never made it out of the mechanical era.

Boston was one of a number of American cities that was able to tune in a new TV station in 1948. But Beantown broadcasts on television pre-dated that by more than 15 years. The station ran into some trouble and never made it out of the mechanical era.

On January 11, 1930, the Federal Radio Commission (according the publication The United States Daily) granted a license to Shortwave and Television Laboratories, Inc., to cover a construction permit for a 500-watt station called W1XAV to broadcast between 2,100 and 2,200 kilocycles. I haven’t been able to determine exactly when the station first went on the air, or sent out programmes on a regular basis, but it was broadcasting by February in conjunction with the NBC Red network station, WEEI.

It was also looking at colour television very early. The Associated Press provided this report in 1930.

Vision In Colors Hope Of Engineers

(By C. E. Butterfield).

Associated Press Radio Editor

BOSTON, May 21 (AP)—Television transmission in colors within two months is the hope of engineers tackling the problem of radio sight in laboratories here.

So successful do they feel they have been in their experimentation that the engineers said they would be able to reproduce colored pictures eight inches square. Included in their development work has been the design of a receiver housed in a console no larger than the ordinary sound set.

If the attempt at color transmission succeeds, it will mark a climax in three years of television work by the Short Wave and Television laboratories, which are operating W1XAV on 137 meters or 2180 kilocycles. The transmitter, designed and built for television work by Hollis S. Baird, chief engineer, has a power of 500 watts.

As one of its accomplishments the laboratory points to its development of horizontal transmission against the former method of vertical transmission. The engineers explained that with vertical transmission a straight line always appears as a curved line with resultant distortion in the received picture. In horizontal transmission a straight line remains a straight line when it is received.

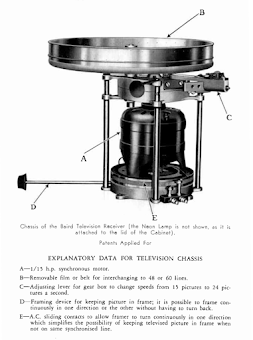

The receiver used is rather novel in that the scanning disk is really not a disk. It consists of a band of metal having a series of holes and is fastened around a drum-like frame which revolves in front of the neon lamp. The band is removable making it possible to change it to receive either s 48-line or a 60-line picture.

The receiver has a framing device which keeps the picture in the correct position for viewing, and which somewhat simplifies synchronization. The framer is controlled by a knob at the front of the receiver. The viewing lens is located just above the tuning and framing controls on a level with the operator’s eyes.

This outfit, the engineers explained, was for television only, and would not reproduce sound, for which a separate set would be required where sound and sight were being received together from the same studio.

Although the picture at present is only four inches square, a process has been developed whereby it can be enlarged to from eight to 12 inches square. Under this method, the engineers said, the picture would be seen on a ground glass rather than through a magnifying lens. They also said that it would be possible for a room full of persons to see the picture at the same time.

In cooperation with WEEI, Boston, W1XAV began sending synchronized voice and vision of the Big Brother club on February 5. Short waves were used for the television signals, and the sound went out on WEEI’s regular wavelength.

The Boston Globe’s radio schedule for the 5th has “Big Brother’s Lighthouse and Coast Guard News Exchange” on from 7 to 7:25 p.m. which included the reading of an episode of “Watchdogs of the Sea” by Douglas H. Shepherd. Big Brother was none other than Bob Emery, later a children’s host on the DuMont Network. The Globe does not mention television.

Baird and his partners must have felt it would be advantageous to have its own radio station to broadcast the sound portion of its TV shows (technology had not been developed to allow audio and video on the same frequency) so it asked the Commission for permission to build one. The request was denied. W1XAV then worked out a deal with the CBS affiliate later in the year.

Television Radio Broadcasting Will Start At Boston

First Programs to Be Given Over Station WNAC on Monday

Boston, Nov. 22.—(AP.)—Radio listeners equipped with television receivers will be able, commencing Monday, to see and hear entertainers in designated programs broadcast from radio station WNAC, through cooperation with television station W1XAV.

Boston, Nov. 22.—(AP.)—Radio listeners equipped with television receivers will be able, commencing Monday, to see and hear entertainers in designated programs broadcast from radio station WNAC, through cooperation with television station W1XAV.John Shepard, 3rd, president of the Shepard Broadcasting Service, which controls WNAC and other stations, announced today that arrangements had just been concluded for simultaneous sound and television broadcasts during two hours each day.

WNAC is in the regular broadcast band sending out its programs on a wave length of 244 meters, while W1XAV sends its television broadcast out on a 141 meter wave. Shepard’s announcement set forth that the television station, the only one of its kind in New England, transmits images that are received easily over a range of 500 miles. The power used is 500 watts. Verification letters have been received from points as far distant as Nova Scotia and Southwestern Pennsylvania.

The first joint programs are to go on the air at noon and 3:30 p. m. From time to time the announcement added, it is expected that additional WNAC programs will be presented from the television station where the main studio has been doubled in anticipation of the new service.

Here’s how the Boston Globe put it the following day:

EXPERIMENTAL PICTURE TRANSMISSION TOMORROW

Experimental television broadcasts are promised the New England radio audience as a result of arrangements made with Station W1XAV, it is announced by John Shepard, 3d, executive in charge of Station WNAC. The first program will be presented tomorrow noon. For the present these experimental television broadcasts will be transmitted during the noonday revue at WNAC and during the WNAC Women’s Federation programs presented daily, except Saturday and Sunday at 3:30 o’clock.

In order to receive these experimental television programs it will be necessary for listeners to equip themselves with special receiving apparatus. Television signals are transmitted on short waves which cannot be received on the usual broadcast receiver. Station W1XAY, from whence the pictures will be sent out, will use a wavelength of 141 meters, while WNAC, which will transmit the sound part of these programs, operates on a broadcast wavelength of 243.8 meters.

There’s no mention of television in the Globe of Monday, November 24, 1930, but the radio listings show the “Noon-day revue” aired from 12:15 to 1 p.m., and the “Women’s Federation” half-hour starting at 3:30 that afternoon featured Mrs. Charles Geissler with lessons on contract bridge, soprano Dorothy French, osteopathic Dr. R. Kendrick Smith, and a Question Box feature.

How long the arrangement with WNAC is also unknown, but the Globe reported on a new audio source on April 21, 1931.

The Federal Radio Commission has granted the Short Wave and Television Laboratories of Boston a construction permit for the erection of a new 30-watt television transmitting station to experiment with television transmission on the ultra-short wave length of 35,300 to 36,200 kilocyc1es and 39,650 to 40,650 kilocycles. Authority was also granted to operate on the frequencies around 43,000, 48,500 and 50,300 kilocycles.

The Boston experimenters thus join the ranks of the small group of research men testing the efficacy of the extremely short waves, roughly between 6 and 8.5 meters, not now covered by international treaty because they have hitherto been regarded as useless.

The commission also licensed the company’s newly built experimental station, W1XAU, to operate with 500 watts on the experimental frequency of 1604 kilocycles, which is to be used as the “sound path” for the television transmissions of W1XAV, which operates on the television band between 50 and 2950 kilocycles, with 500 watts power. A renewal license was granted for the latter station.

In mid-December 1930, the FRC had reassigned the station to the band between 2850 and 2950 kilocycles.

The New York Sun of July 18, 1931 stated W1XAV was now on the air Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights, 7:30 to 10:30 p.m., broadcasting only films. But there was at least one popular on-location programme. This is from the Globe of October 2, 1931.

The New York Sun of July 18, 1931 stated W1XAV was now on the air Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights, 7:30 to 10:30 p.m., broadcasting only films. But there was at least one popular on-location programme. This is from the Globe of October 2, 1931.

Doors Locked to Keep Our Overflow Audience

By LLOYD G. GREENE

Regardless of the status of television, a much debated topic these days, there is no denying the fact that it was the one attraction which drew visitors en masse at the Boston Radio Show last night in Horticultural Hall. The hall in which the television exhibition was held proved inadequate to admit at one time all who wished to witness the visual broadcast sent out from Station W1XAV of Boston at 7:30 o’clock.

For sometime before the demonstration was scheduled to take place interested spectators gathered outside the doors. When the time arrived for the program to start so many were on hand that it became imperative after admitting them to the capacity of the hall to close the doors to avoid overcrowding. Thus, in relays, did the Boston public witness its first demonstration of reception over a receiver constructed and proportioned along lines which reasonably forecasts the home visual receiving instrument of the future.

Dai Buell on Air

The first public demonstration of television in New England proved as magnetic in the talent it drew before the televisor, for it brought back to radio Dai Buell, a concert pianist of international fame, whose first radio appearance dates back to Nov. 1, 1921; Dorothy George, mezzo soprano, and Frances Foskette, soprano—all of whom are members of the People’s Symphony Orchestra and have also sung in the leading light opera companies and symphony orchestras of the country.

It was Miss Buell’s keen interest in television as a new medium destined to bring the fine arts to the public, and the fact that television is still in its non-commercial stage, that prompted her to consent to play for the demonstration at the Radio Show. In an interview before the broadcast she expressed the opinion that there is a tremendous Interest in watching a noted pianist play as well as listen to him.

Proof of this, she said, was to be found in the great demand for seats on the stage at Symphony Hall performance. The animation of moving fingers, their expectant poise for the beginning note of some intense passage—all add color to a piano recital. Television, she stated, will for the first time permit this part of piano recital to come to the public as well as the music itself.

Miss Buell’s highly developed fingering technique was visible over the air to those who heard her play last night. The program, like that of her first radio recital, was in the nature of her “Causerie Concerts,” a type of program which is enhanced by the interspersing of interpretative comments on the composition played.

The Sun schedule of January 14, 1933 shows the station had expanded to “experimental programs” Monday through Saturday from 8 to 9 p.m. with a “sketch” on Saturdays from 9 to 10. The station’s license was up for renewal that April, but an examiner with the radio commission said “no” because of insider trading. Here’s the December 31, 1932 edition of the NAB’s Broadcaster’s News.

Recommendation was made (Report No. 440) this week by Examiner Elmer W. Pratt that the application of the Shortwave Broadcasting Corporation for experimental relay broadcasting license for Station W1XAL, be denied; that the application of the Shortwave & Television Laboratory, Inc., for renewal of experimental visual broadcasting license for Station W1XAV be denied; and, that the application of the same corporation for experimental television license for Station W1XG and renewal of special experimental license for Station W1XAU be denied.

The Examiner states that "it appearing that the Shortwave & Television Corporation has completely absorbed the Shortwave & Television Laboratory, Inc.," * * * that license renewals would be contrary to provisions of the Radio Act and "the policy of the Commission to grant renewal licenses only to the party actually operating the station involved."

It is further stated by the Examiner that "Shortwave & Television Corporation is now illegally engaged in operating two stations (W1XAL of the Shortwave Broadcasting Corporation and W1XAV, of the Shortwave & Television Laboratory, Inc.) and proposes to continue their operation should their applications be granted." He recommends against granting any of the applications.

Baird’s company evidently won an appeal because the Commission granted license renewals on April 28, 1933 to both W1XAV and portable station W1XG—but only until July 1st. An article in the November 1939 edition of Communications magazine says the station went off the air in 1933, but published summaries of FRC and FCC decisions show that W1XAV wound up with Shepard Broadcasting, owners of WNAC. Shepard was granted a renewal of a special experimental license on August 28, 1934 for broadcasting at 61,500 kilocycles at 100 watts, though it was for short wave broadcasts only. FCC granted an application on February 21, 1936 with the abbreviation “License exp.” A story in All-Wave Radio in its December 1937 still was operational, without regular hours. True or not, Boston’s pioneer TV days had ended.

Reportedly, after Shortwave and Television Laboratory dissolved operations in 1935, Baird and his colleagues founded a new company called General Television Corporation, ditching mechanical and moving to electronic television. He was reportedly broadcasting experimental television programs in Boston as late as 1941 on channel 1, when he folded the company after negotiations with 20th Century-Fox and others to buy the station fell through. After General Television, too, was shuttered in 1941, Hollis Baird moved on to a career as an educator. He taught electrical engineering and physics at Northeastern University’s Lincoln Institute, starting in 1942 as part of the Engineering, Science, and Management War Training program. He retired in 1976 after a long career as professor and administrator. He died in 1990.

ReplyDelete